Some people describe it as an emotional heaviness that doesn’t lift. Others experience it as unpredictable shifts—feeling deeply low one moment, then strangely elevated or irritable the next. Living with a mood disorder can feel like being caught in an emotional tide you didn’t ask for, pulled along by something invisible but very real.

It’s easy to minimize emotional pain, especially when it’s not visible. But mood disorders can be just as disruptive and exhausting as any physical illness. They affect how we move through the world—our energy, our thoughts, our relationships, and even our sense of self. And when your own mind feels like unfamiliar territory, it’s hard to know where to begin or how to explain it to anyone else.

What is a Mood Disorder?

Mood disorders are mental health conditions that primarily affect a person’s emotional state. That might sound simple on the surface, but the experience itself is rarely so clear-cut. These conditions often involve persistent sadness, low motivation, hopelessness, or emotional extremes that don’t match what’s happening around you. For some, it shows up as long periods of depression. For others, it might look like cycles of high energy, impulsivity, and irritability followed by emotional crashes.

It’s not just about “being sad” or “having a bad day.” A mood disorder can last for weeks, months, or even years—interfering with work, relationships, sleep, appetite, and the ability to enjoy things that once felt good. And because mood disorders vary widely, two people can have the same diagnosis but experience it very differently.

Depression and bipolar disorder are the most well-known examples, but there are also less commonly discussed types, like cyclothymia and dysthymia (now called persistent depressive disorder). Some people live with symptoms for years before they even realize there’s a name for what they’re feeling.

Causes of Mood Disorders

- Biological factors

- Disruptions in brain chemistry (especially serotonin, dopamine, and other neurotransmitters) can significantly affect mood regulation.

- Hormonal imbalances or neurological differences may contribute to chronic emotional instability.

- Disruptions in brain chemistry (especially serotonin, dopamine, and other neurotransmitters) can significantly affect mood regulation.

- Genetics

- A family history of mood disorders can increase vulnerability, although it doesn’t guarantee someone will develop one.

- Genetic predisposition often interacts with life experiences and environment.

- A family history of mood disorders can increase vulnerability, although it doesn’t guarantee someone will develop one.

- Early trauma and chronic stress

- Emotional, physical, or sexual trauma—especially in childhood—can alter how the brain processes stress long-term.

- Prolonged stress from grief, loss, instability, or conflict may also trigger mood symptoms.

- Emotional, physical, or sexual trauma—especially in childhood—can alter how the brain processes stress long-term.

- Medical conditions and medications

- Chronic illnesses like thyroid disorders or chronic pain can influence emotional well-being.

- Some medications have mood-related side effects that can mimic or worsen symptoms.

- Chronic illnesses like thyroid disorders or chronic pain can influence emotional well-being.

- Substance use

- Alcohol, stimulants, or other drugs can mask or intensify underlying emotional patterns.

- In some cases, substance use becomes intertwined with undiagnosed or untreated mood disorders.

- Alcohol, stimulants, or other drugs can mask or intensify underlying emotional patterns.

What is Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder?

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD) is a relatively newer diagnosis that typically affects children and adolescents. It’s characterized by intense irritability, frequent temper outbursts, and ongoing difficulty managing emotions in a way that’s developmentally appropriate.

It’s more than just being moody or acting out. These children often feel like they’re constantly on edge, with emotions that boil over quickly and intensely. Outbursts might happen several times a week—or even daily—and in between, there’s often a low tolerance for frustration and ongoing irritability that affects home, school, and social life.

Many kids with DMDD are misdiagnosed early on, often with ADHD or oppositional defiant disorder. While symptoms can overlap, the emotional reactivity in DMDD is more persistent and severe. This can lead to strained relationships with parents, teachers, and peers—adding layers of shame or confusion to what the child is already experiencing internally.

It’s important to approach DMDD with empathy, not just discipline. These children aren’t trying to be difficult—they’re struggling with emotional regulation at a foundational level. Early diagnosis and treatment can make a big difference in helping them build those skills and reduce the intensity of their emotional experiences.

Mood Disorders Treatment

- Psychotherapy (Talk Therapy)

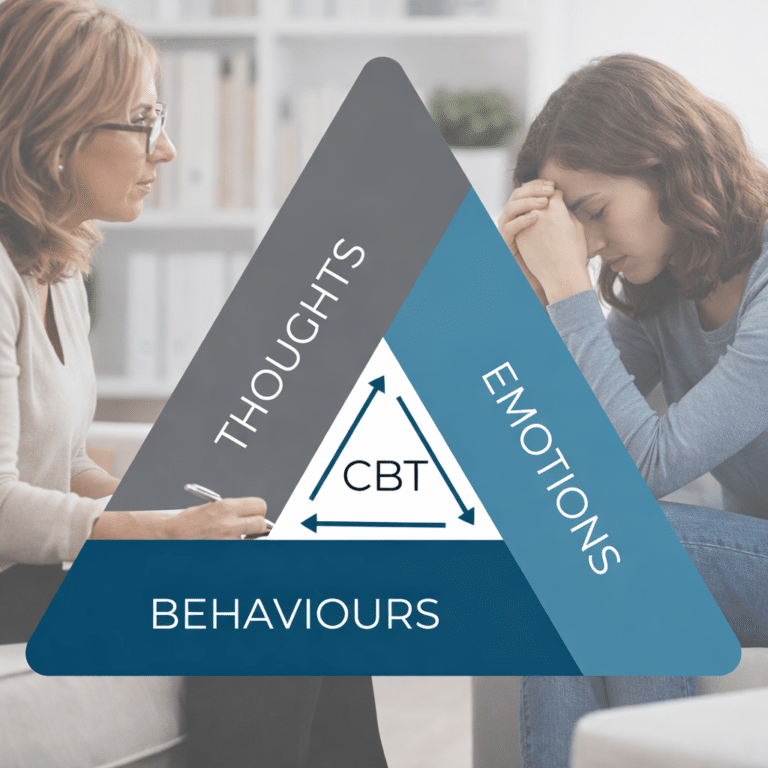

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps identify thought patterns, regulate emotions, and build healthier coping tools.

- Therapy also creates space for processing difficult emotions without fear of judgment.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps identify thought patterns, regulate emotions, and build healthier coping tools.

- Medication support

- Antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or antipsychotic medications may be prescribed based on diagnosis and symptom profile.

- Medication is not a cure-all but can be stabilizing enough to support progress in therapy and daily functioning.

- Antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or antipsychotic medications may be prescribed based on diagnosis and symptom profile.

- Lifestyle and behavioral strategies

- Prioritizing sleep, regular movement, and consistent meals can support emotional regulation.

- Building daily structure—even small routines—can reduce unpredictability and emotional overwhelm.

- Prioritizing sleep, regular movement, and consistent meals can support emotional regulation.

- Social connection and support systems

- Isolation can deepen symptoms, while meaningful relationships can offer a buffer against emotional lows.

- Whether through friends, support groups, or therapy, connection matters.

- Isolation can deepen symptoms, while meaningful relationships can offer a buffer against emotional lows.

- Long-term care and follow-up

- Mood disorders are often chronic, but manageable.

- Ongoing care—whether through therapy, medication reviews, or wellness check-ins—helps maintain stability and catch early signs of relapse.

- Mood disorders are often chronic, but manageable.

Final Thoughts

Mood disorders don’t always show up in obvious ways. Sometimes they look like irritability, fatigue, or withdrawal from things that used to feel good. Other times, it’s an emotional intensity that feels impossible to contain—or explain.

Whatever shape it takes, struggling with your mood isn’t a sign of weakness. It’s a sign that something inside you is asking for care and attention. And while the path to feeling better may not be immediate, it’s absolutely possible—with the right support, the right tools, and enough time.

Responsibly edited by AI

Other Blog Posts in

Animo Sano Psychiatry is open for patients in North Carolina, Georgia and Tennessee. If you’d like to schedule an appointment, please contact us.

Get Access to Behavioral Health Care

Let’s take your first step towards. Press the button to get started. We’ll be back to you as soon as possible.ecovery, together.